“Nine Inch Nails,” Trent Reznor once told us, “is not a band. And it’s not a democracy.”

The NIN frontman is one of the great auteur rock’n’roll stars. There aren’t many like him. He has collaborators and hired hands, but his music is ultimately his great and magnificent vision.

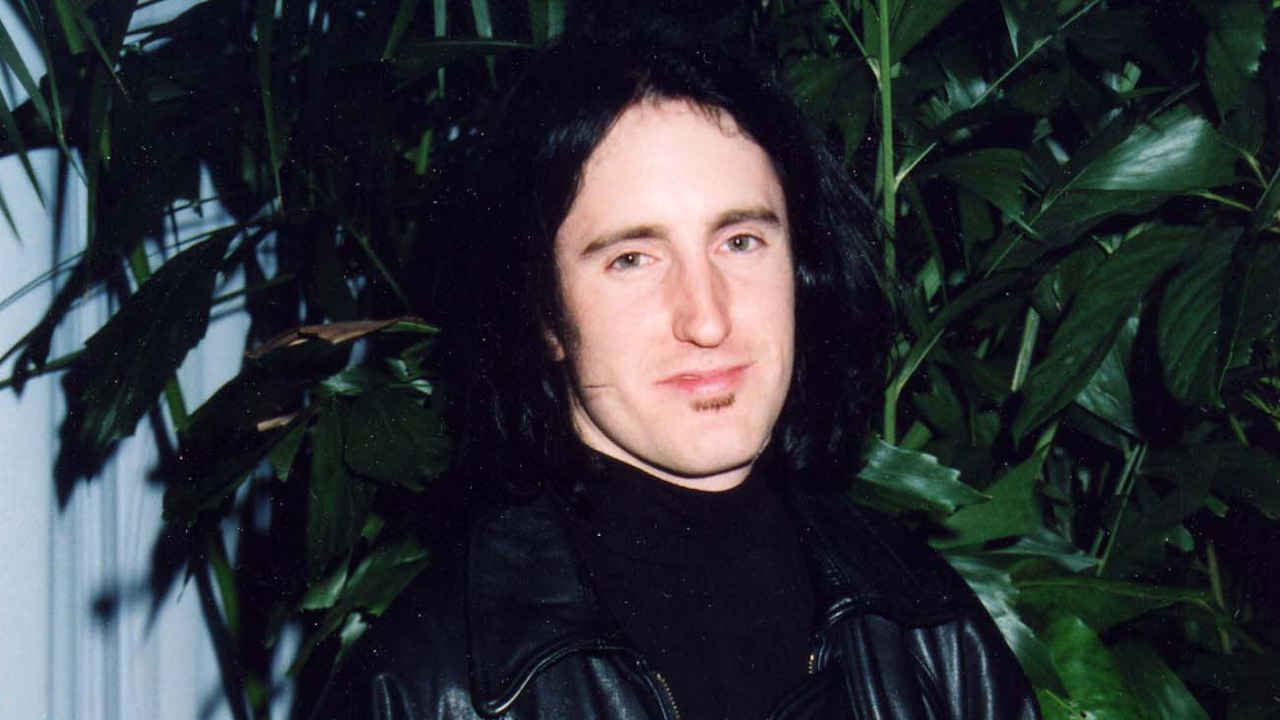

Yet to look at that solid-looking guy in the tux collecting the Oscar for his soundtrack to 2010 movie The Social Network, you wouldn’t think that he was once the most notorious chemically enhanced rock’n’roll murder-junkies in all of creation. He was once the apotheosis of the clad-in-black pale Byronic rock star.

In the 90s you couldn’t move for pasty- faced, angsty pretty boys with guitars and ‘issues’. But Trent took these first-world blues to a much higher level. NIN’s second album, The Downward Spiral, is still one of great black suns around which all troubled teens and would-be rebel angels circle. It was a plunge into the shadows that, by rights, should have destroyed its creator. In 1994, just after Kurt Cobain killed himself, the question on everyone’s lips was ‘Who’s next?’ Top of the list was Trent. Suicide or overdose or plane crash: he was odds-on favourite to join that stupid club. But thankfully, that’s not how it turned out.

Had things gone differently, Trent would probably have still made his living in music, though probably as a producer or engineer rather than as a rock star. After dropping out of college, he got a gig as an assistant engineer in a studio in Cleveland. Much of his time was spent cleaning the place. A trained pianist, he could read music and find his way around a Chopin concerto. He had ideas about writing songs and making his own music and, with the permission of the studio’s owner, he started work on some demos that would be the basis for the first Nine Inch Nails album, Pretty Hate Machine. Although he had been in bands at college, Trent had problems finding other musicians to help him work out the sound he had in his head. So, like his hero Prince, he played all the instruments himself apart from drums.

“I grew up in a little town in the middle of nowhere, pre-internet, pre-college radio,” he said. “My input for the first 16, 17 years of my life was AM radio, FM radio. Pretty mainstream stuff. I think growing up on a diet of melodic-based pop music instilled in me that format of hooks. As I started writing music, and considering how to write music, it would come back to something that was memorable. I tried to think in terms of choruses, hooks and melodies – even if that was set in a very noisy, atonal environment.”

Those early demos got a lot of interest, and in 1988 he signed a deal with TVT Records, a label whose bread and butter was albums of themes from popular TV shows. Although it got his music out to a wide mainstream audience, it was a deal that he would come to regret.

Pretty Hate Machine, recorded in 1988 and released the following year, was essentially an electronic work influenced by Skinny Puppy, Ministry and Depeche Mode, with Trent as a one- man band. Industrial music had been growling away in the underground for over a decade and although the album was well received, it’s highly doubtful that many people seriously thought that this would be anything but another record for shaven-headed cyber-goths to cut themselves to.

In a nod to Depeche Mode, Trent adopted a numbering system for all his releases. Depeche Mode’s designation system was STUMM for albums, BONG for singles. Trent adopted Halo, so debut single Down In It was Halo 1, Pretty Hate Machine was Halo 2 etc.

The early live shows were disastrous. Trent assembled a live trio – himself on guitar and vocals, Chris Vrenna on synths and Ron Musarra on drums – to support Skinny Puppy. They were kicked off the bill after a couple of weeks. The lineup was rejigged with Chris moving to percussion and they played a number of poorly received support slots in the US, but somewhere along the line, probably when they went out on the first Lollapalooza tour, they started to get good. Really good.

“Our show got more anger-oriented, rather than ‘We want to do a fine job for everybody’ – ‘Fuck you! Like our music or we’re going to fucking spit beer on you and insult you,’” he said. “When you do, they love you more, then that makes you have less respect for them. It fuels itself to where you just turn into something else. It’s a weird thing.”.

Nine Inch Nails made their live debut supporting Guns N’ Roses at Wembley in 1991. They were eagerly anticipated, if only by a hardcore clique of fans, critics and music business types. Watching Trent looking isolated and unsure onstage in front of thousands of baying big-haired bozos – with just the odd smattering of skinheads in trenchcoats and mirrorshades in the crowd – it was hard to see what all the fuss was about. Offstage, he was determined to bomb away the memories of the show with liquor.

Pretty Hate Machine was successful enough for his label to putting pressure on him to deliver a follow-up. The abrasive mini-album Broken introduced distorted guitars and a more hard rock sensibility. Despite the fact that he was no stranger to MTV, it still largely appealed to a cult market, the industrial underground. In ’92 Trent moved to LA. After years of bitter and draining legal tussles with TVT he had just signed a deal with Interscope that gave him the artistic freedom that he needed to work on the album that would become The Downward Spiral. By that time, rock’s centre of gravity had shifted under the influence of everything from Nirvana Rage Against The Machine to post-Black Album Metallica and Nine Inch Nails themselves. The world, it seemed, had relocated territory Trent himself had helped stake out.

The Downward Spiral was one of the first albums to be recorded entirely using what was then state of the art digital technology whereby sounds were recorded and stored on a computer hard drive rather than on analogue tape. They could then be digitally altered – adding effects, reverb or taking such effects off and cleaning the sound up where necessary - rather than just putting the band in the studio, recording the instruments and mixing it all together.

The beauty of digital recording is that it can really be done anywhere. The location Trent wanted had to be sufficiently isolated but large enough to accommodate the gear and any collaborators like producer Flood and his main collaborator/assistant drummer Chris Vrenna. Chris’s job was to sift through hundreds of videos for samples to be used on the album.

He found a house to rent in the Hollywood Hills, a ranch-style bungalow on Cielo Drive. It’s a beautiful location, set in the real super-rich LA populated by movie executives, actresses and musicians. The house had had some famous tenants in the past, most notably Polish film director Roman Polanski his pretty young wife, actress Sharon Tate. It also had a dark history – in August 1969, five people, including Tate, were murdered by followers of Charles Manson. It seemed to dovetail perfectly with Reznor’s worldview. “It’s a coincidence. When I found out what it was, it was even cooler,” he told Rolling Stone at the time. Later, he admitted that he had deliberately chosen it for the bad vibes but regretted this after a meeting with Sharon’s sister, Doris.

At the time they were recording in the house, Chris and Trent nicknamed the studio ‘le pig’, alluding to the word ‘pig’ scrawled on the wall in Sharon Tate’s blood by killer Susan Atkins. One of the strongest tracks on the album was also March Of The Pigs, though Trent denied that there was any connection between this and Manson.

The Downward Spiral wasn’t planned as a concept album, but there are linking themes and recurring motifs in the songs. Trent had been keeping notes on his inner state since his chaotic booze- and chemical-fuelled stint on Lollapalooza. This provided the conceptual backbone for the songs: “It is personal experiences, but wrapped up in the pretentious idea of a record with some sort of theme or flow. It’s become a kind of a dated 70s concept, but some of the records that influenced me on this album were [David Bowie’s] Low and even The Wall – I’m sure I’m ripping off Pink Floyd… in fact, I know I am ripping them off. There’s records, although they may appear dated today, that try to do things that are more exciting to me than, ‘Here’s my video track and here’s my dance song and here’s my power ballad.’ All that kind of disposability. It was just me bored, trying to come up with something that I kind of wanted to set the parameters to work within, to focus more.”

After years of work on the album alternating with more sex, drugs and booze, The Downward Spiral was released in 1994 and became the soundtrack of a generation. In 1997, Trent was named one of Time magazine’s 25 most influential people, sharing the honour with the cartoon character Dilbert and then-US Secretary Of State Madeleine Albright. He was called “the anti-Bon Jovi” by Time. His “vulnerable vocals and accessible lyrics led an Industrial revolution: He gave the gloomy genre a human heart… his music is filthy, brutish stuff, oozing with aberrant sex, suicidal melancholy and violent misanthropy. But to the depressed, his music proffers pop’s perpetual message of hope: There is worse pain in the world than yours. It is a lesson as old as Robert Johnson’s blues.”

He was top of the world, but the work and the touring and the sheer weight of expectations was taking its toll. Trent had become a celebrity, known by people who had probably never heard a note of his work. He started working on soundtracks such as Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers and David Lynch’s Lost Highway. He was in demand as a collaborator and remixer. But these were all sideshows. People wanted the next album and Trent was uncertain if he even wanted to go on.

“I could be onstage in front of thousands of fans, singing my music back to me, and I’d feel empty and miserable,” he said.

Angry and discontented, burned out after the process of recording The Downward Spiral and keeping up a punishing touring schedule, he eventually started work on the follow-up. In 1998, he relocated to New Orleans and became a virtual shutaway in the studio, working with producer Alan Moulder who’d worked on the mixes of The Downward Spiral, but whose pedigree also included Depeche Mode and My Bloody Valentine, who Trent admired.

Chris Vrenna and Trent had parted ways after the gruelling and knowingly-titled Self-Destruct tour in support of The Downward Spiral. Ministry drummer Bill Rieflin and then Jerome Dillon joined him along with Charlie Clouser and Danny Lohner as well as guests such as King Crimson/David Bowie guitarist Adrian Belew and Page Hamilton, guitarist with Helmet. But the bulk of the album was recorded by Trent on his own.

With The Fragile, Trent succeeded in making a great album, but one that was in the shadow of its predecessor, commercially and artistically. Meanwhile, his personal life continued to spiral out of control. He’d been to rehab and cleaned up his act, but before long returned to his former ways. In July 2000 he was hospitalised after accidentally overdosing on heroin and cancelling a major London show. It was, he said, a wake-up call. The following year he entered a rehab centre in New Orleans.

Newly sober, he finished work on a live DVD called And All That Could Have Been. He also began work on other projects such as Tapeworm, a collaboration with Tool frontman Maynard James Keenan. He also went into the studio with Rage Against The Machine frontman Zack de la Rocha to produce a solo album. Neither went well: the Tapeworm recordings were unsatisfactory and the solo album was stillborn.

Public attention focussed on Trent again thanks in part to the success of Johnny Cash’s acclaimed cover of Hurt, a stark, self-lacerating ballad from The Downward Spiral. Initially bemused, Trent said he was moved to tears by the video for the song. In 2004 he started work on a new NIN album, With Teeth, but he was not confident. “I didn’t start work assuming that I still had the power that I once wielded,” he said.

The album marked the beginning of his collaboration with engineer, mixer and producer Atticus Ross. Although it began life as a concept album, With Teeth was a song-oriented record, simpler and less grandiose than The Fragile. Released in 2005, it was also more political, catching some of the post-September 11 mood of paranoia – themes that came to fruition on the follow-up Year Zero.

Recorded and released less than two years after With Teeth, Year Zero was largely written on the tour to promote its predecessor. The concept, about a future theocratic tyranny, was wide ranging: as well as the album there was a game involving websites and emails, USB drives left at gig venues that contained tracks from the album as well as intriguing messages and web links. Naturally these leaked online resulting in friction with US music industry watchdog the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). It was all great promotion, even although Trent denied that that is what it was.

“It’s not a promo gimmick to get you to buy stuff, he said. “This is the art.”

With his Interscope contract at an end, Trent released the enigmatic ambient work Ghosts I-IV, which was available in a variety of packages and formats whose price ranged up to US$300.

NIN’s seventh album, 2008’s The Slip, was distributed free as a download from the band’s website, without any advertisement or warning. If Ghosts I-IV bore little resemblance to what had gone before, The Slip seemed to consciously hark back to the harsh industrial stomp of Pretty Hate Machine and The Downward Spiral. It was a fan-pleaser – and, according to Reznor, it marked the beginning of a period where NIN would “disappear for a while”. There was even a ‘farewell tour’ (which turned out to be nothing of the sort, of course).

But Trent’s interests were definitely shifting. The soundtracks for director David Fincher’s The Social Network and The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo made him an in-demand Hollywood composer. He also formed a band called How To Destroy Angels with his wife Mariqueen Maandig, Atticus Ross and artist Rob Sheridan. Their debut album, Welcome Oblivion, was released in 2013.

Except the Nine Inch Nails story wasn’t over. In 2012, Reznor announced that he was back in the studio working on new Nine Inch Nails music, which would be released as 2013’s Hesitation Marks album. Since then, he’s been incredibly prolific, balancing a stream of NIN releases (the Not The Actual Events/Add Violence/Bad Witch triptych of EPs released between 2016 and 2018, plus 2020’s experimental Ghosts V and Ghosts VI albums) with scores and soundtracks for everything from post-apocalyptic horror Bird Box to Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Mutant Mayhem.

The Nine Inch Nails of today are a very different proposition to the Nine Inch Nails of Pretty Hate Machine and The Downward Spiral. And so is Trent Reznor – he’s the rare musician who has continually reinvented himself and been at the forefront of new ways for artists to engage with an audience. Whatever the future holds, it proves that not dying was the best move he ever made.

Originally published in Metal Hammer issue 242. Updated in May 2024